Thanks to a connection made at a RECLAIM NYC meetup, salvaged materials became a key part of the renovation of the parish house at St. Michael’s Episcopal Church, helping preserve the building’s historic character, minimizing the project’s environmental footprint and social risks, and supporting local business.

Renovating to Serve the Community

St. Michael’s has stood on the corner of Amsterdam Avenue and 99th Street on Manhattan’s Upper West Side since 1807 and its landmarked Romanesque building dates back to 1891. The church plays an important role in the neighborhood, hosting community programs including a soup kitchen, food pantry, 12-step meetings and a Spanish-language preschool.

The church is currently undergoing a multi-phase renovation, beginning with accessibility upgrades. Two ramps and an elevator are being added so community members with mobility challenges can more easily enter and navigate through the building.

More Blocks Needed!

Building a ramp from the sidewalk down to the bottom-floor entrance to the parish house required excavating into the church garden and constructing new retaining walls on both sides. The new ramp replaces a sidewalk-level path with stairs bordered by knee-height walls made of Belgian Block, also known as sett or jumbo cobblestone.

Before: The old pathway to the parish house prior to renovation (Photo: Walter Cain)

The project team decided to deconstruct and reuse blocks from the existing knee walls but there were not enough of them to build the much deeper retaining walls. An additional source of blocks had to be found.

Belgian Blocks from the old knee wall deconstructed and stacked on site (Photo: Walter Cain)

New or Used?

Newly-hewn Belgian Blocks can be easily sourced in New York City. They are available from wholesalers, garden centers and home improvement retailers in a range of shades that approximately match historic blocks.

While the exact origin of a new block sold in the US can be hard to trace, there’s a good chance it will have been quarried in India, by far the world’s biggest granite exporter. Inexpensive labor and the low cost of transoceanic shipping make it more cost-efficient to import granite from India than to quarry it in the United States. Quarrying the granite requires fossil fuel-powered tools and shipping it over long distances further adds to carbon emissions.

New Belgian Blocks (Photo: Chief Bricks)

But there is an alternative source of Belgian Block: the streets of New York City.

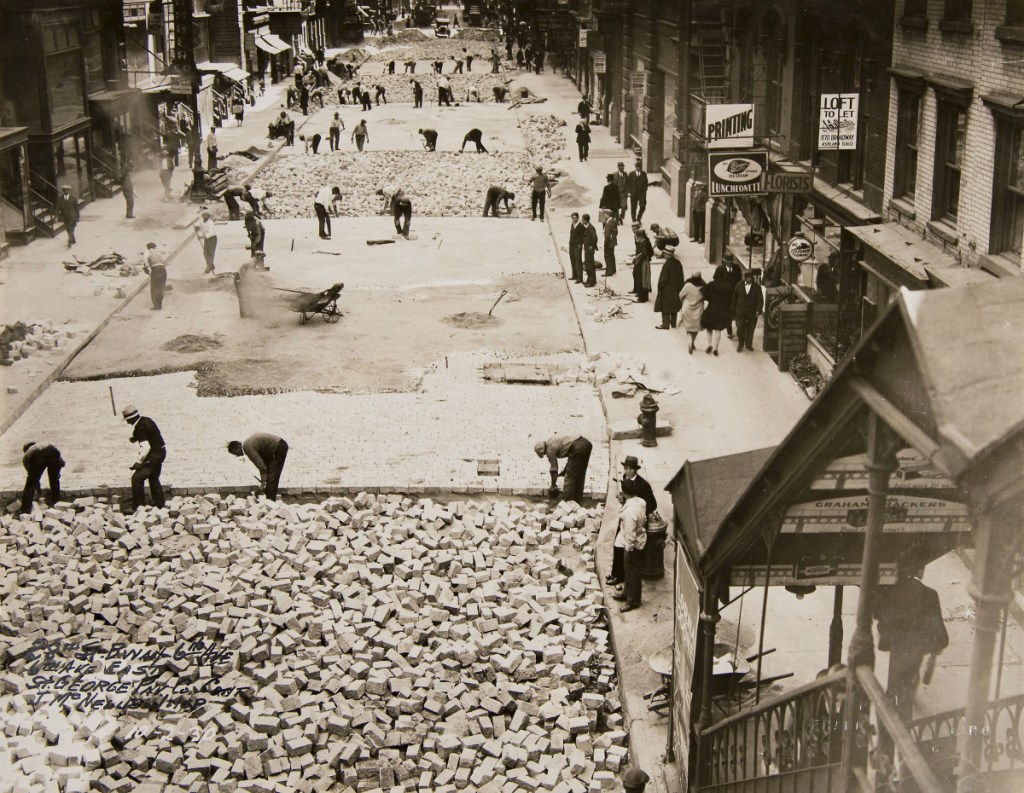

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Belgian Block quarried in New England gained popularity as a road paver, replacing natural cobblestones thanks to its flatter and smoother surface.

Workers rebuilding the road surface of 28th St with Belgian Blocks, 1930 (Photo: NYC Municipal Archives)

Belgian Blocks later fell out of favor to asphalt, which provided a much smoother and easier-to-maintain surface. According to a 2017 study of NYC’s Belgian Block heritage, in 1949, 140 miles of road in NYC were paved with Belgian Block but in 2014, only about 15 miles remained. Even in historic districts, it can be challenging to retain historic Belgian Block because it is not bike-friendly and is too uneven to meet accessibility requirements for walkable surfaces in the Americans with Disabilities Act.

Uneven Belgian Blocks on a street in Tribeca (photo: Willem Boning)

Much of the Belgian Block removed in NYC street renovation projects is crushed into low-value aggregate or sent to landfill. But a few local brick and stone companies salvage historic Belgian Blocks and resell it.

Finding a Source

Walter Cain, an architect helping St. Michael’s manage their project designed by Richard McElhiney Architects, met Alkis Valentin, owner of Chief Bricks, at a RECLAIM NYC meetup and learned that his company sells reclaimed Belgian Block. Chief Bricks collects the blocks from road demolition contractors, cleans them, separates them by size and color and palletizes them.

L: Processing salvaged Belgian Blocks at Chief Bricks R: Reclaimed Belgian Blocks (photos: Chief Bricks)

Thanks to Chief Bricks’ careful sorting process, it was easy to find an exact match for the Belgian Block dismantled from the St. Michael’s knee wall.

Mixing Old with Old

Chief Bricks delivered seven pallets of reclaimed Belgian Blocks to the St. Michael’s Church site to make up the full height of the new retaining walls.

To create a seamless blend between the historic blocks deconstructed on site and the additional historic blocks from Chief Bricks, workers from general contractor Cypress Restoration expertly mixed the two sources together. In the completed retaining walls, it’s impossible to tell which blocks came from where, helping the walls blend into the historic context of the site.

The new retaining wall on one side of the ramp (Photo: Chief Bricks)

The Benefits Of Salvage

Sourcing salvaged Belgian Blocks for the St. Michael’s Church project came with a number of advantages compared to sourcing new blocks.

First are the environmental benefits. Reusing blocks dug up from city streets diverts material that would otherwise go to landfill or be crushed into low-value aggregate. Digging up, moving and reassembling blocks all within NYC requires a small amount of energy compared to the high embodied carbon required to quarry new blocks and transport them from overseas.

Second are the social benefits. Sourcing salvaged blocks in NYC supports more local jobs and local businesses compared to importing new blocks from overseas.

Third are preservation and aesthetic benefits. Salvaged Belgian Blocks proved to be a much better visual match to the historical knee wall blocks at St. Michael’s Church than new blocks, which would come close but would still be easily distinguishable.

Challenges For Scaling Up

Among masonry units, salvaged Belgian Block has a good market value because it is durable, aesthetically appealing and desirable for historic preservation projects. Despite the shrinking length of NYC roadways paved with Belgian Block, supply should continue to be available in the future through other sources such as private driveways.

But according to Valentin, there are two main challenges to scaling up the reuse of Belgian Blocks:

1. Generating demand. US buyers still predominantly seek out new blocks and may not even be aware that salvaged blocks are available on the market.

2. Connecting supply to demand. Historically, the salvaged masonry market has operated informally through personal contacts, eBay and Facebook Marketplace, leading to problems of inconsistent supply, black market dealings, mismatched expectations, and scams. These problems present barriers to entry for new buyers and have limited the growth of the market.

To address these problems, Chief Bricks is taking a more professionalized and customer-focused approach to the reclaimed masonry market, providing transparent pricing, detailed product images and next-day delivery. This approach helped pave the way for reuse on the St. Michael’s Church project and is attracting a diverse range of new customers.

If you have ideas for how we can continue to scale up reuse in New York City, please join us at our next Reclaim NYC meetup!

Reclaimed Materials List

Belgian Blocks: 350 ft2 (840 stones)

Further reading

St. Michael’s Church renovation project

Toward Accessible Historic Streetscapes: A Study of New York City’s Belgian Block Heritage

Project Information

Location: 225 W 99th St, New York, NY

Year Completed: 2025

Typology: Worship space / community facility

Project Scope: Renovation

Reclaimed Materials: Belgian Blocks

Project Team:

Architect: Richard McElhiney Architects

General Contractor: Cypress Restoration

Project Manager: Walter Cain

Reuse Partners:

Belgian Blocks provided by Chief Bricks

t

er